RECENT INTERVIEWS

November 29, 2021: SD Voyager, Hidden Gems: Daily Inspiration: Meet Tania Pryputniewicz. My gratitude goes to Stephanie Hernandez for this interview (covers my connection to tarot’s healing power, poetry, childhood’s connection to a commune, and a light-hearted honeymoon revenge story).

January 2021: Coronado Times interview, by Alyssa K. Burns, Coronado Author Tania Pryputniewicz Releases “Heart’s Compass Tarot” This Valentine’s Day

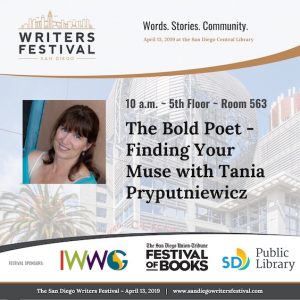

The Inaugural 2019 San Diego Writer’s Festival, held at the downtown San Diego Public Library brought together over 80 presenters and teachers to bring free presentations and classes to the community. Susan J. Farese of SJF Communications interviewed participating writers about their current projects and take on the San Diego writing community. Read more here: Author Interview with Tania Pryputniewicz

The Inaugural 2019 San Diego Writer’s Festival, held at the downtown San Diego Public Library brought together over 80 presenters and teachers to bring free presentations and classes to the community. Susan J. Farese of SJF Communications interviewed participating writers about their current projects and take on the San Diego writing community. Read more here: Author Interview with Tania Pryputniewicz

PODCASTS

Girl Talk

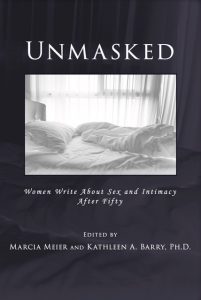

Girl Talk podcast hosted by Weeping Willow Books editor and publisher Marcia Meier with a focus on “some serious talk about aging and sexuality.” Meier points out that, “Women over 50 virtually disappear in our youth-obsessed culture…” but turns it around with her biweekly podcast. In this October 2018 episode, Tania reads from her non-fiction contribution to the anthology, Unmasked: Women Write About Sex and Intimacy After Fifty and discusses creative ways to sequester time to foster intimacy in a household with three children and their hammers.

Girl Talk with Poet and Mom Tania Pryputniewicz

Related: Taos News, “Nothing to Hide: SOMOS hosts reading about intimacy in the Golden Years,” by Laura Bulkin

This Choice

March 2016 Podcast interview conducted by Ren Powell (on becoming a poet, a mother, a lover of Tarot Writing; includes a reading of “There is No Frigate like a Book” by Emily Dickinson and “God’s in the Butter” (from “November Butterfly”): This Choice Tania Pryputniewicz

REVIEWS, NOVEMBER BUTTERFLY (POETRY)

REVIEWS, NOVEMBER BUTTERFLY (POETRY)

If there is truth to Pryputniewicz’s voice, and I believe there is, it is in her search for the beauty to be found in dark places. Certainly her title poem reflects that, as she takes “…a butterfly with a frayed / wing pinned living / to the windshield” and makes the gesture of liberating that wounded yet vibrant creature. It is a liberation of all our wounded selves and our sorrows.—Read the full review by Susan Schoch, Story Circle Book Reviews, author of The Clay Connection: Jim and Nan McKinnell, June 4, 2015.

“November Butterfly” is an often surprising process of recovery that finds empowerment and strength through the field of mothering, and healing through the act of creating – a commendable and memorable debut. —Read the full review by Lauren Gordon, Damfino Press, author of Meaningful Fingers, Knocking at the Door, and Keen, March 12, 2014.

Despite the outward appearance that she might be damaged because of her sex and the damage done to her because of her sex, she refuses to kowtow to this negativity, instead preferring to “look you/ in the unblinking amber screen/ of your eye.” She sees the amber glow of the sun in the self—the warmth of what is possible. —Read the full review by Anne Marie Fowler, The Mom Egg, January 14, 2015.

Pryputniewicz’ Guinevere is opinionated and strong compared to Marilyn and is a direct contrast to the helpless heroine she is in medieval poetry.—Read the full review by Jen Teeter-Moore at The California Journal of Women Writers, by Jen Teeter-Moore, February 2, 2015.

Poets and Poems: Tania Pryputniewicz and “November Butterfly”—By Glynn Young, April 7, 2015.

TRANSLATIONS

Poems from November Butterfly have been translated into Italian at Patria Letteratura by Alessandra Bava: Sylvia (Part III), Corridor, and Joan, 21st Century

and into Danish by Cindy Lynn Brown for a reading at Odense Lyrik 2018 (Odense Denmark). Here’s a link to the sound file of Ulla Krogh-Henriksen reading Brown’s translation of Corridor.

INTERVIEWS

San Diego Writers, Ink: What is/was your favorite part about including famous females like Marilyn Monroe or Joan of Arc into your poetry, as you do in your first poetry collection, November Butterfly?

Tania Pryputniewicz: Including famous women gave me a chance to continue a conversation they started with our culture and with us about what it means to be female, powerful, charismatic and vulnerable. I could riff, for example, on Joan of Arc’s renegade relationship to her spirituality and call it part of a “disintegrate spin of ecstasy.” I could listen to Marilyn; might she have said from the “other side,” “No girl sets out to die?” I describe that kind of listening and imagining into the lives of others as a form of astral rubbernecking in a post I wrote before book tour last year.—Read full interview at San Diego Writers, Ink, by Casey Cromwell.

TCJWW: How are all of the women in your poems connected?

Pryputniewicz: They are all daughters. Some are also mothers. They are all creators. The inquiry their finished creative work undertakes (via poem, sculpture, painting, or journey) matters as much as the story of what each woman overcame to get to the page, her airplane, her canvas, or what it took to break free of roles, perpetrators or lovers. Or, in the case of Thumbelina or the sisters in The Three Oranges, their imagined inquiry towards agency.

Take for example Jay DeFeo’s painting “The Rose,” which DeFeo called Deathrose and White Rose, to finally settle on simply, “The Rose.” That three title progression and her years of layering paint, wood and mica to that canvas could be said to sum up a journey many women go through in relation to their own bodies, if you consider “The Rose” as a metaphor for the female nexus: We attract lovers and hunters in a society where the line between sex and death blurs easily and girls, by media, are sexualized at younger and younger ages. Conversely, that same gateway possesses a pure potential to birth, to bring in a new life (White Rose). And yet all along that range of potential, ways of experiencing our female sexuality lives inside of us, just like DeFeo’s rose ultimately encompasses various versions of truth/inquiry she lived through on her way to creating and applying that nearly 2,000 pounds of paint to the Deathrose/White Rose/Rose. I was moved by the long entombment of “The Rose” in a basement and its eventual resurrection (Jay DeFeo and The Rose, edited by Jane Green and Leah Levy). Just as it took all manner of luminaries to resurrect that painting, it will take a cross section from each sector of society to heal what we’ve done to women and men with our polarizations, which do neither sex good.

Simarly, in the poem Marilyn, I couldn’t get the image of Marilyn the night she stopped breathing out of my head; the image felt psychologically resonant to me and accurate for women in my generation: the reverse birth image of woman as hummingbird, her tiny hovering head and the labial petals consuming her as if she were suffused and drowning in the very feminine that I so wished had been hers to command for longer.

—Read the full interview at TCJWW, February 20, 2015, Jen Teeter-Moore

THREE QUESTIONS: TANIA PRYPUTNIEWICZ

THREE QUESTIONS: TANIA PRYPUTNIEWICZ

Interview by Jenn Monroe, Sept 28, 2015, originally published by dailydoseoflit (now-off-line)

It was my own (and one of our poetry editors) fascination and love for Guinevere that pulled me head first into your poems. What is it about her that attracts you? Why did you feel compelled to tell us more about her story?

My poet friend Jayne Benjulian asked me the same thing when I was firing off Guinevere poem after Guinevere poem to her as I was trying to finish the book. “What sets her apart?” Jayne asked. “Why Guinevere and not someone else?” I answered in the poem, “What Sets Her Apart, Asks Jayne Reading Another Guinevere Poem for me in Massachusetts,” referencing the eclectic companions (Arthur, Mordred, Morgayne, Merlin) in her life, the physical world she lived in (“the rain stippled Severn, / orchard’s apples rinsed silver by dawn”), and the love triangle (“Her position / middle star of Orion’s belt, between Arthur and Lancelot”).

An additional gift was a sliver of experience in Guinevere’s history that intersected with a childhood rape I was struggling to address in poetry. Guinevere first came alive in my psyche tangentially when my father passed me a copy of T.H. White’s The Once and Future King. Later in college, I loved the way Marion Zimmer Bradley inhabited the female leads of Camelot in The Mists of Avalon.

Guinevere found me again just after graduate school in the heartland, when a childhood friend proposed to me. He saw Sir Edmond Blair Leighton’s drawing, “The Accolade” (which we construed to depict Guinevere knighting a kneeling Lancelot) in my home, which I’d brought home from the crystal and gem store where I worked part time in Iowa City. He playfully suggested that we marry in costume. What poet could refuse?

So I married in Guinevere’s dress. Our seamstress also fashioned a tunic out of red pigskin leather over which she sewed Leighton’s fiery eagle/dragon emblem for my husband-to-be. Many of our guests came in costume and we married in a redwood grove to the sound of a Hermit thrush’s trill, a harp, and bagpipes for the closing processional.

Like many other couples we weathered the dual joy and stress that accompanies parenthood—and the tests that fall in the “happily ever after” part of marriage—yet the safety and structure of marriage allowed me to begin writing about the past trauma of the rape.

At a low point in our marriage, Persia Woolley’s Guinevere Trilogy (Child of the Northern Spring, Queen of the Summer Stars, and Guinevere, The Legend in Autumn) landed in my hands. The frank, forthright first person Guinevere in the books moved me deeply; especially the way Woolley wrote the scene of entrapment and physical trespass in which Melwas overtakes Guinevere.

When I contacted Woolley to thank her for her books and for the way she handled that specific scene, she wrote back to say that it was “the rape sequence…[that] was the final thing that convinced [her] to write the story from [Guinevere’s] point of view.” She also wrote about the possible connection she believes might exist between Guinevere’s apparent inability to have children and the rape, if Pelvic Inflammatory Disease ensued. I published her full comment in a post on one of my blogs, “Revising Guinevere: Ten Writers Transforming Rape, or When Trees Mattered More Than Boys.”

Prior to encountering Woolley’s Guinevere, I had finished “Mordred’s Dream,” “The Corridor,” and “Totem.” Woolley’s work gave me psychological access to go back in to early notes and initial drafts of the half dozen or more poems I needed to finish to round out Section II including “Veil,” “Veil II” and “Transport.” Mercifully, by the last poem, “Guinevere, 4:33 a.m., San Diego, California,” Guinevere is on her way to saying goodbye. Standing at the foot of my bed in present time “for the first time the outlines of her dress blur / like milkweed tufts loosed from grip of pod.” Of course I don’t really believe she is fading away entirely, not after this long of a psychological love affair—she’ll be back when she has something more to say. And I would never turn her away.

What an intense relationship! What do you think allows her to resonate with 21st century readers? Why do you think she still reveals herself to us today?

Love triangles never seem to go out of vogue. Or tales of women so desirable they are abducted, start wars, and leave disaster in their wake. And maybe because we are moving politically into a time when more women are holding public positions of power we are curious about the historical context of power just as we’ve increasingly looked at point of view and questioned the authorship of those points of view to seek out a multiplicity of histories.

I imagine Guinevere still reveals herself to us because the imagery that comes with her position in time still has more to offer. I owe this idea to Dion Fortun’s book, Glastonbury: Avalon of the Heart. I love that Fortun’s title acknowledges the physical landscape the Arthurian Legends call home and its attendant living matrix of memory and simultaneously addresses the possibility of a landscape in our bodies: an Avalon of the Heart. I’m thinking also of the Holy Grail and metaphors of the internal and external search for spiritual peace.

I love to ask students and friends about their mentors, either based in literature or real persons, from any time period in history to play precisely with this issue of resonance. Why are we attracted to certain people or characters? I’m not advocating searching for the “Holy Grail” in the form of another person, but advocating sustained inquiry to discover the nature of the resonance for how it might inspire us to grow or reach past our own burdens.

I experienced this directly when I stepped in to first person and Guinevere spoke from the end of my bed. When she said, “I am the White Rose of Glastonbury,” I realized it is possible to come back from anything, from any trauma. As the rose that blooms in winter, Guinevere has become for me a symbol of hope.

Do you search for opportunities to share hope in your work? Sometimes I believe poetry gets a bad reputation for being all bleak (even though there is real truth there). How can poetry be a source for Hope without becoming sentimental?

I don’t think it is a conscious goal for me, at least not at the outset of creating new work, to write poems that inspire hope. Depending on which Alice has a hold of me, I fall down the rabbit hole, like other poets, not to arrive at anything inherently hopeful or familiar, but to answer questions or explore obsessions rooted in the masked, underlying psychological realm of collective unconsciousness. That kind of exploratory excavation can lend itself to some bleak work, but I do hope my poems offer something genuine and worthwhile. I told my father-in-law to drink a glass of wine when he cracked open November Butterfly and warned him that as much as I wanted the collection to be all butterflies and roses, it wasn’t.

I take solace (and find hope) in the visceral, gritty poetry of Dickinson, Gluck, Lorde, Shockley, Rich, and Olds for example; their work is luminary because it does not flinch. If you set out explicitly to inspire hope, there’s the danger of drawing on the saccharine familiar, if that is what you mean by sentimental. As in writing from the first ring associations one has regarding puppies, babies, rainbows, butterflies and lovers. Go down the rabbit hole with that same list of topics into subsequent rings of inquiry and you stand a chance of writing non-sentimental poems that help readers connect in unexpected ways to their interior life. And it follows that greater intimacy and insight in relation to the self affords us the hope for blossoming collectively.

AWARDS

Two Gardens, from Berkeley Postcard, winner of Rockvale Writers’ Colony 2019 time-themed poetry contest. Publication and residency in Tennessee at Rockvale Writers’ Colony.

Berkeley Postcard, finalist, 2018 Comstock Writers Group Chapbook Contest.

My Geppetto, finalist, 2016 Fairytale Review poetry prize.

Marg Chandler Memorial Fellowship. A Room of Her Own Foundation 2015 Retreat Ghost Ranch, New Mexico. Presentation: Mothers and Daughters: Secret Catharsis in Woman Warrior. Workshop: Writing Through Fear: Free Your Butterfly.

Black Angel: Scripted, Never Shot in Soundings East, runner up for the Claire Keyes Poetry Prize, 2014.

My Bedroom, My Sister, in Snow Jewel, Grey Sparrow Press, Third Place, Poetry/Flash Competition, Five Year Publication of Snow Jewel by Grey Sparrow Press, Fall 2014.

Poetry movies, She Dressed in a Hurry (for Lady Diana), Amelia, and Nefertiti Among Us, Juror’s Best of Show, 2D/3D visual poetry show held at the LH Horton Jr Gallery at San Joaquin Delta College, curated by Chandra Cerrito.

God’s in the butter, Eugene Ruggles Award for Poetry, The Dickens, 2005; co-winner.